Archetypes in Myths General Mythological Symbols and Their Meanings

The formation of myth was a kind of research. Myths that helped people relate to their reality became trusted and were orally transmitted from generation to generation, until they were written down Ė if not replaced by other myths along the way, and forgotten. So, myths have their own evolutionary law, their own survival of the fittest. Those that gain trust are enforced, also improved as human experience increases. The ones that for one reason or other become less convincing will be discarded. Their purpose is to shed some light on what to make of it all. Some elements and themes came rather naturally, because of what could be observed already by primordial man. Dreams made him aware of something existing apart from the palpable world his body inhabited. So, myths emerged about what existed beyond and around what the eyes could see. People died, but were remembered as clearly as if they still walked beside their survivors. So, there were myths to explain what had become of them, because they clearly had not disappeared completely even after their bodies decayed into dust. And people were born out of the bellies of their mothers, soon growing just as big as them. Myths were needed to explain it. Also, during their lives, fate struck people very differently, rewarding some tremendously and striking down hard on others. Again, myths were made to explain it. The earthly life and its burdens raised numerous questions. So did the sky high above their heads. The sun with its warmth and light appeared and disappeared daily, whereas the moon moved differently and its light was as cold as it was weak in comparison. Not only that, but in the cluster of little white dots on the night sky, some moved and the others did not. Myths took care of that. The greatest mystery of all was from where it all came. Had there been a beginning, and if so, what caused it? One woman out of whose womb the first child fell Ė but if so, where did that woman come from? One man, whose seed had planted that first child in its motherís womb Ė but again, where would that man have come from? One first morning enlightened by the sun, but out of what did the sun originally emerge? This was the greatest challenge for myth to meet, and many myths did. Some did it well enough to survive for thousands of years. A few of them are still around. Some of these myths, but not as many as one might think, also dealt with the possible future end of it all.

Whatever primordial man wondered about, could be dealt with in a myth. So, their number increased, as did their complexity. They gave solace and a comforting feeling of life making sense. This was a need of the mind, satisfied by the very capacity of the mind that created the need.

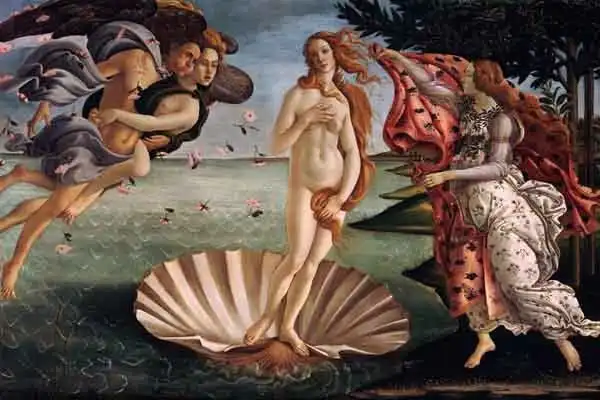

ArchetypesMyths have themes. They are stories dealing with specific subjects, the roots of which have been described above. But stories also have characters, and in the case of myths they are often representing much more than a single person doing this or that at a whim or from some basic human need. They are not just types, but archetypes.Itís a term from Ancient Greece, signifying what we would call a prototype, a model on which other things are based. It doesnít necessarily refer to characters in a play. Plato meant that behind the real world, there are ideal forms from which our world finds its shapes. The use of the term archetype for myth and drama was made popular by the psychoanalyst C. G. Jung, who presented his application of it in 1919. He found patterns in folklore, myth, and art, from which he extracted several symbolical types, characters carrying certain meanings, which could be explained as different aspects of the human mentality. He claimed that these archetypes are the same through history and in every culture, almost as if included in the human genome. By studying the archetypes and their meanings, we can learn to understand ourselves. That can be discussed. The patterns he found might instead have been those of characters and roles necessary in drama, with which mankind has been occupied for thousands of years. Some of the archetypes are easily recognized from the recurring characters in drama history: the king, the mother, the sage, the hero, the villain, and so on. Itís a bit like the chicken or the egg, though. Jung would have claimed that the archetypes were there before the drama, which had to incorporate them in order to enthrall the audience. Indeed, drama as well as literature carried the insights of psychology long before the science of it was invented. An anthropologist might remind us that human life revolves around certain social roles, ever since we got this gargantuan brain of ours. There are mothers, fathers, and children. There are also leaders, advisors, priests, warriors, heroes and cowards, followers and agitators, artists, dreamers, wanderers, hunters, lovers, and so on and so forth. Each one of us has bits and pieces of it all. Anyway, the idea of the archetype is as interesting in psychology as it is in drama. Myth, it seems, is full of them, the larger than life characters proudly carrying their sharply chiseled traits. Those who really excel at their archetypes are usually called gods in the myths. If we extract the archetypes from a myth or a play, we see the plot more clearly and understand their actions better. We also become aware of the patterns by which life tends to repeat itself whenever and wherever. The human condition can be described through archetypes, which are necessities by which our actions and our sentiments are governed. For example, any child can find that the dependency of the mother may become a burden of which one needs to rid oneself, and the admiration of the father easily becomes a rivalry of sorts, maybe even contempt at length. Itís part of growing up. Thatís also the core of what Jung meant the archetypes to be: clues to self-realization. A leader is sort of the father of fathers, and the leader of leaders we call god, whether imagined or not. A hero is what we want to be, but we canít if the hero we look up to is constantly guarding our safety, doing the heroic deeds for us. An adversary angers us, but would we ever move an inch if not confronted by one? And no adversary is more persistent than the one each of us carries in our mind. A lover is sweet, but never as sweet as when we are the reciprocal object of that love. And how easily love turns into the opposite! Indeed, there are patterns by which we live, and as Shakespeare said:

Jung on the ArchetypesIf you want to read more about the archetypes, please go to my text about C. G. Jung and his treatment of the subject. It's on another website of mine. Click on the header to get there.

This text is a chapter in my book Tarot Unfolded from 2012, which discusses the archetypes and symbolic images present in the Tarot deck of cards.

MENUCreation Myths Around the WorldHow stories of the beginning began.

The Meanings of MythologyTheories through history about myth and fable.

Archetypes in MythsThe mythological symbols and what they stand for.

The Logics of MythPatterns of creation.

ContactAbout Cookies

CREATION MYTHS IN DEPTHCreation in Rig Veda 10:129The paradox of origin, according to an Indian myth.

Genesis 1The first creation story of the bible scrutinized.

Enuma ElishThe ancient Babylonian creation myth.

Xingu Creation of ManThe insoluble solitude of gods and humans.

ON MY OTHER WEBSITESPsychoanalysis of MythWhat Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung thought about myths, their origins and meanings.

Myth of CreationAn introduction to the subject of creation myths and the patterns of thought they reveal.

Cosmos of the AncientsWhat the Greek philosophers believed about the cosmos, their religion and their gods.

Life EnergyThe many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

TaoisticTaoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy of life explained. Also, the complete classic text Tao Te Ching online.

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Sunday Brunch with the World Maker

Sunday Brunch with the World Maker Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd