Creation Myths

|

by Stefan Stenudd |

Making any definition of what religion is, independently of Christianity, is just as difficult as it is meaningless. The same is true for the concept god, or deity, as well as worship and sacred.

Also the term 'belief' is something very vague and fleeing. Modern religion in industrial society uses the word almost as a paradox. Confessing the belief in something implies that reason would lead to disbelief. It's a commitment to believing in something one really can’t believe.

This would have made no sense at all to Homo rudis. At the birth of a creation myth or any other cosmological speculation, reason was probably not challenged at all by these ideas, or they would not have remained.

Doubt

As for the offspring of Homo rudis in the millennia to follow, the ancient myths were definitely questioned even in societies where they were still kept alive and officially confessed.This can be observed in the writings of the ancient Greek philosophers, who lived in a world where mythology was definitely cherished and worshiped. Still, many philosophers were both willing and able to question them, partially or completely.

Applying the triangle of functions above, it's clear that the Greeks mostly praised the norms of the myths and their artistic value, but they hesitated about their explanatory reliability. Some philosophers also debated their moral content.

What has lasted the longest in the Greek myths is definitely their artistic value.

Homo rudis, though, must have believed in the myths of his own creation, or he would have altered them. They must have made sense to him, which does not necessarily mean that he regarded them with the trust that we have for mathematical formulas. He believed in them insomuch as he found them likelier than other theories he might have come up with. Well, likelier or more meaningful or more exciting, to put it in the triangle of functions.

The actual purpose of Homo rudis for inventing a creation myth is out of our reach. Its enigma is comparable to that of the Neanderthal burial of their dead and the question if it is proof of some kind of religious belief or not. In the latter case, the only clues are how these graves were arranged and what can be read from this. As for the creation myths, their plots and ingredients may reveal to what extent they were explanatory, moral tales, or mere entertainment.

But the concepts of belief and religion add very little to our understanding of them.

Actually, what is there in religion outside the triangle of functions described above? The only true connection between religion and creation myths might be that their functions can be divided similarly. In the case of religion as we know it today, the trio of functions adds up to one overall need for religion to fulfill – that of consolation. That can be said about creation myths, too.

So, what religion and creation myths reveal about one another is the basic human need behind both, and therefore something about the thought patterns leading to them. But one is not the explanation of the other, nor the source of it.

The Evolution of Creation Myths

As mentioned above, the creation myths we know may not be the authentic ones, but versions altered through the centuries before they were written down in the sources at our disposal.Alterations would have been made along the three directions of the triangle of functions. A shifting understanding of the world and its emergence would change the myth's explanation, modified norms of the society keeping it alive would change its message and morals, and new tastes of the audience would bring out other twists to the drama of it. Wherever the need for change was the greatest, the myth would be altered the most.

Such changes may be difficult to detect and extract in their entirety, but they are not completely unnoticeable. They would leave scars and tiny anomalies, peculiarities that seem to distort the imagery of the myth, or inconsistencies that raise questions the myth leaves unanswered – some more obvious than others. Each anomaly gives its own clue to which of the three kinds of functions instigated the change. The history of the society in question, if known in enough detail, would reveal the same.

A clear example of these dynamics is Enuma Elish, the Babylonian creation epic with Sumerian roots, where the Babylonian god Marduk conquers the gods of the older tradition, and becomes the supreme deity. Marduk then creates mankind as mere servants to the gods, just like that society had its rulers who treated the whole population as their servants.

Marduk kills the old creator goddess Tiamat.

One would wonder why the Babylonians did not simply make a new creation story, where Marduk was the unchallenged ruler of all from the outset. But at that time both the gods of old and their process of world creation were already familiar to the people, so a fresh start would only lead to two competing creation myths – weakening the trust in both. The Babylonians needed to adjust the old myth, because they had already adapted it.

This was probably the case whenever a change in society called for change in how it perceived and described creation. Traditional myths could not be eradicated, so the new needs had to merge with the old stories, altering some things but saving enough of the old version to keep consistency from the past toward the future. The greater the theme of a story, the greater the work to have it changed, and creation myths are by definition among the greatest stories told.

These dynamics of myth have been explored and recognized within the history of religion, and there are many examples of how such changes can be reversed in search for the original version.

Still, this has mostly been done without applying narration aspects. The revised version makes less instead of more sense. Also the explanatory aspects have often been neglected, if not ignored, as if creation stories had nothing to do with describing a possible creation of the world.

What have been emphasized the most are the norms and moral implications, because these are widely seen as forming the core of religion. That’s a simplification quickly bringing the exploration of creation myths to a halt.

Subconscious Creation

Most, if not all, theories on the emergence of creation myths have taken for granted that they were not invented in intentional acts of conscious minds. Instead, they have been explained as expressions of basic needs of people – such as the need to worship in order to find solace, the need to explain the unknown to stop fearing it, or emotional urges rising from the unconscious.In these perspectives, the creation myths have been regarded as expressions of religious beliefs, where the latter was presumed to forego the former.

In the 19th and early 20th century, there were debates about what “primitive man” was able to fathom, and what may have been the steps in the presumed evolution of religions. Creation myths studied in this context were interpreted according to the level of evolution they were thought to represent, where those supposed to be the oldest were denied any abstract or intellectually advanced content. That made the reading of them quite superficial.

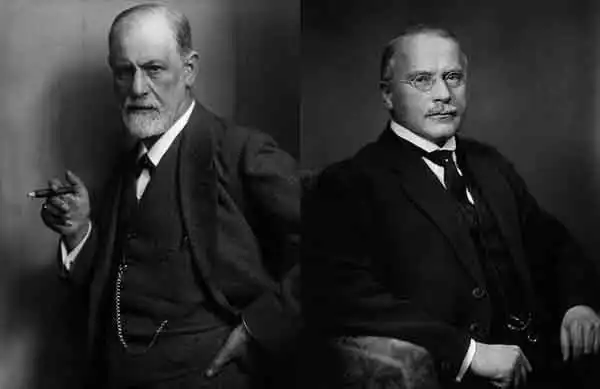

In the first half of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud and Carl G. Jung formed theories by which to interpret religions and their myths as expressions of subconscious human needs.

Sigmund Freud (left) and C.G. Jung.

Freud saw religion as the constant repetition of repent for a primordial patricide, so he searched the myths for little more than examples of that drama and the guilt it would have brought. Jung, on the other hand, explored the myths at much greater depth. To him, they were representations of the archetypes, basic universal symbols of elements in man’s quest for self-realization.

In Jung’s perspective, the creation myths were of particular interest, since they dealt with birth and rebirth, and events that set the rules for human life thereafter. He and his followers – a mighty number of researchers, particularly in the mid 20th century – sorted the creation myths into categories of archetypal significance. What they read into the myths, they did not presume to be elements intentionally included in them by their original creators, but unavoidable components because of the nature of the human mind.

Jung's idea of the archetypes as patterns through all mythological material actually shows similarities to dramaturgical components proving to be unavoidable in story-telling. In the latter case, the reasons are the dynamics and excitement needed for a story to attract an audience, whether they are aware of it or not. So, there is an unconscious ingredient in that model, too – but on the side of the audience, and not on that of the author. Strong arguments are needed to claim that the inventor of a story is unaware of the choice of its components and the progression of its plot.

In the late 20th century there have emerged other more or less psychological theories about how myths have been formed, for example those based on cognitive psychology, or on the mechanics of metaphors, investigated by linguists. They also presume that such influences have mainly been unawares.

They have so many similarities with the Jungian perspective on myths that they can be described as variations of the Jungian paradigm – especially in their presumption that significant ingredients of great meaning were included in the myths without the conscious intent of their inventors.

There is no clear indicator of Homo rudis lacking the willful intent of the conscious mind that modern man is credited with. Our predecessors were able to come up with quite sophisticated and intriguing myths. The refinement of their stories argues for greater mental capacities than the above mentioned theories are prepared to grant them.

The only shortcoming of Homo rudis’ mind that we can be certain about is its lack of knowledge of the scientific discoveries we have at our hands to describe the world and its inner workings. His explanations were based on very little else than his own observations, and those of the people in his immediate surroundings.

But from that experience he would have been able to consciously invent a creation story, fully aware of the choices he made for its components and events. Otherwise he would not have been able to communicate it to his fellow men. Nobody disputes that the telling of a story is a conscious act, so why would not the invention of it be?

Next

- Introduction

- Man, Too

- Human Thought Revealed

- Trusting Creation Myths

- Time and Place

- Authenticity

- Inner Story Logics

- Function

- Triangle of Functions

- The Relief of Tragedy

- Homo Rudis

- Present Day Tribes

- Belief

- Doubt

- The Evolution of Creation Myths

- Subconscious Creation

- Simplicity and Urgency

- The All Was Born in the Past

- Originality

- Religion, Science, or Art

- What Can Be Reached

This text was written as an introduction of sorts to my ongoing dissertation on creation myths, at the Lund University History of Ideas and Learning.

Some of My Books:Click the image to see the book at Amazon (paid link).

The Greek philosophers and what they thought about cosmology, myth, and the gods. |

MENU

Creation Myths Around the World

How stories of the beginning began.

The Meanings of Mythology

Theories through history about myth and fable.

Archetypes in Myths

The mythological symbols and what they stand for.

The Logics of Myth

Patterns of creation.

CREATION MYTHS IN DEPTH

Creation in Rig Veda 10:129

The paradox of origin, according to an Indian myth.

Genesis 1

The first creation story of the bible scrutinized.

Enuma Elish

The ancient Babylonian creation myth.

Xingu Creation of Man

The insoluble solitude of gods and humans.

Contact

About Cookies

ON MY OTHER WEBSITES

Freudian Theories on Myth and Religion

The writings by Sigmund Freud and other Freudians on mythology and religion examined.

Jungian Theories on Myth and Religion

The writings by Carl G. Jung and other Jungians on mythology and religion examined.

Myth of Creation

An introduction to the subject of creation myths and the patterns of thought they reveal.

Cosmos of the Ancients

What the Greek philosophers believed about the cosmos, their religion and their gods.

Life Energy

The many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

Taoistic

Taoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy of life explained. Also, the complete classic text Tao Te Ching online.

Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd

About me

I'm a Swedish author and historian of ideas, researching the thought patterns in creation myths. I've also written books about Taoism, the Tarot, and life force concepts around the world. Click the image to get to my personal website.

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Sunday Brunch with the World Maker

Sunday Brunch with the World Maker Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes