The Logics of MythBasic Patterns of Creation Myths

1 Myth: Six CriteriaOddly, determining what is a myth of creation is much easier than to define what is a myth. There have been numerous attempts of the latter, differing considerably both in substance and in success. It might very well be that one will have to settle with trying to state it by exclusion — what is not a myth.

This is also often the case with stories of different kinds — many of them are easily distinguished as not being myths, while the ones remaining can always be questioned as to whether they are adequately to be labeled myths. In the following, I wish to sort by exclusion. What does not meet with all the demands below, is not a myth. What does meet with the demands, on the other hand, may very well be one — or point out the need for additional demands. What does not meet with these criteria, is not a myth:

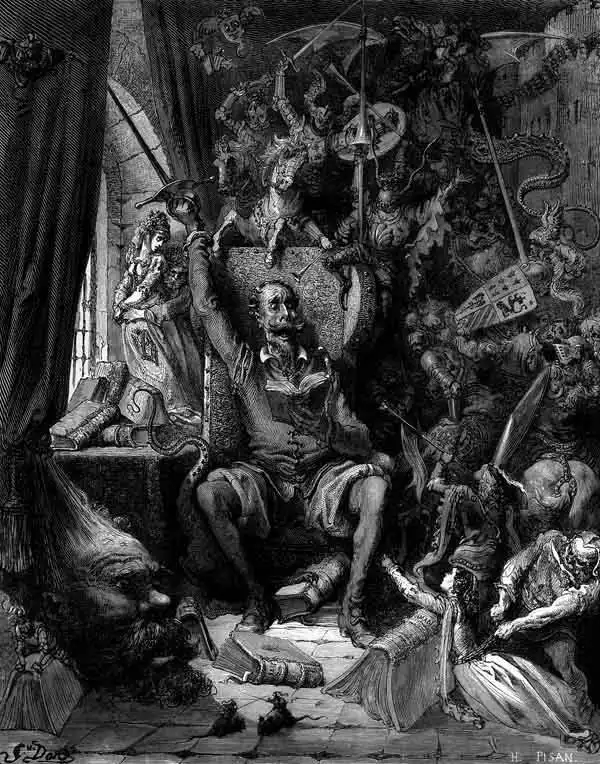

Don Quixote. Book illustration by Gustave Doré, 1863. Don QuixoteSo how about Don Quixote by Cervantes? It passes criteria one, two, three, but stumbles on four — the story does not claim to be one of actual events, nor is it traditionally told in that way. The fifth condition it might pass, somehow, but it definitely does not pass the sixth, since this story has its known original author. Thus, it is not a myth. The same would then be the case with most works of fiction — except if they are expressly based on stories which precede the author's version.

Le Morte d'ArthurThat would, for example, be Le Morte d'Arthur, written by Sir Thomas Malory but based — at least major parts of it — on traditions preceding him. This tale, then, easily passes criteria one through four, whereas it partly passes the fifth, in so much as there are many ingredients in the story not being regarded as likely to actually having taken place. The sixth criterion it passes too, although it is safe to assume that many parts of the story are Malory's own inventions. One might say, then, that Le Morte d'Arthur contains both fictional elements, of one author's origin, not passing all the criteria, and other elements which do, thereby qualifying as myths.A number of tales of times long gone have been preserved by historians of the past, telling vividly about kings and heroes who are said to have walked the earth in a distant past from which there are no remnants. Would such chronicles pass as myths? The stories of Arthur and his knights of the round table seem to be myths to the extent they are unlikely to actually having taken place, and this varies from one episode to the next in Malory's text, but there are numerous examples of historical writings without any so called supernatural ingredients, and yet, historians of today doubt their accuracy. This doubt, though, is not what I mean with the expression 'strong sense of unlikeliness' in the fifth criterion. It should not merely be regarded as questionable, but rather quite unthinkable — closer to impossible than to improbable.

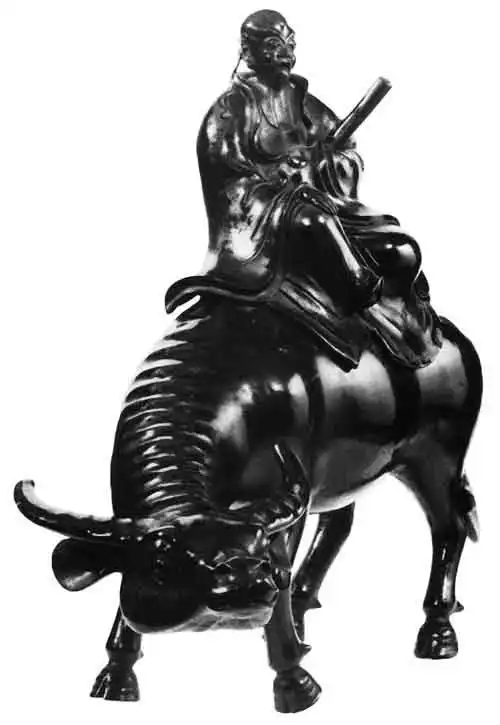

Lao TzuFor example, when the Chinese tradition has it that Lao Tzu, alleged writer of the Tao Te Ching, rode away from his high position at the emperor's court on the back of a water buffalo, writing down his classic upon the request of a guard at the border, impressed by his wisdom, and then to disappear into unknown lands, this may all seem improbable to historians and the general public alike — but impossible it is to none. There is no strong sense of unlikeliness regarding this story, so it does not qualify as a myth. Nor does the fact that most historians doubt Lao Tzu's ever having existed change this.

Lao Tzu, legendary writer of the Tao Te Ching, leaves China on a water buffalo. Chinese bronze figure from the 17th century The Chinese historian Ssu-ma Ch'ien, whose historical chronicles from about 90 BC tell the above and more about Lao Tzu, differs clearly from Malory in the respect that he states nothing about the legendary figure, which we would regard as supernatural. In his text Lao Tzu is portayed as a wonderfully wise man, but not at all magically so. Ch'ien has Kung Fu Tzu say about him, after their meeting, that Lao Tzu in his splendid wisdom is like a dragon — but only metaphorically, no hint at all that he would really be such a beast. Although the experts claim it to be even more unlikely that Lao Tzu — if he ever existed — would have met with Kung Fu Tzu, this is still not unlikely enough to make it a myth, since there is nothing impossible about it. The fifth criterion might be more sharp an instrument of exclusion, if the term unlikeliness would be changed into impossibility, but that would cause several additional and more difficult distinctions to be made. What is regarded as impossible differs so much from person to person and from one time to another, it is not a dependable instrument. Yet, most people who would hesitate to judge something as impossible, are not as hesitant to use the term unlikely — I dare say that the latter will find much more consensus than the former, whatever the phenomenon or object to be labeled might be.

IcarusSome tales we generally regard as myths, so if they are excluded by the criteria above, there must be a need for revising them. Icarus, whose manmade wings melted when he flew too close to the sun, would without controversy be labeled a myth. It easily passes criteria one through four and six, whereas one need to ponder the fifth criterion some. In the time of ancient Greece, there might very well have been numerous people believing — at least somewhat — in the authenticity of the story, but would not people of other cultures, even at that time, have regarded it as highly unlikely? Certainly we do so today, to us it seems much closer to impossible than to improbable, indeed. This raises an interesting possibility, a dynamics in time, where a story may very well be classified as seemingly actual history in one era, but become a myth in another period. This could also be happening in the reverse order, so that myth later on becomes reality — were we, for example, suddenly to discover a species of lizards the size of elephants, with a fiery breath, or the ruins of a city of formidable architecture and refinement on the bottom of the Atlantic ocean.

AtlantisAtlantis, the sunken city of an ancient advanced society, is also swiftly passing every criterion but the fifth. Such a city may be unlikely, but not even to our minds altogether impossible. We still have in somewhat fresh memory the discovery of Troy. Still, just as the ruins of Troy do not convince us of a mighty battle between men and gods in its surroundings, the possibility of a sunken city in the ocean does not encompass an equal likeliness for it being of such splendor and majestic fate as that alleged to Atlantis. So, Atlantis will pass as a myth — until there are findings giving substance both to its existence and magnificence.

Urban mythsThe second criterion opposes some contemporary uses of the term, such as the concept of the modern urban myths — oral traditions of today, about horrors and wonders supposed to exist in the shady corners of our society. Not dealing with a distant past, they cannot qualify as myths in the above definition. The use of the term for contemporary phenomena implies that they are essentially the same as myths of old — born out of and nourished by the same patterns of human thinking. This is not at all certain. Until such a relation has been established, we benefit more from keeping a distinction between the two.

AhasverusThere are obvious similarities between those modern hearsay, to try another term for them, and some equally spectacular hearsay of the past. Ahasverus, doomed to walk the earth without rest, has certainly played a role comparable to that of the crocodile popping up from water closets in modern hearsay, such as being rumored to have appeared here and there. On the other hand, Ahasverus has a story linked to him, whereas many of the modern hearsay have not — at least not of any elaborate nature. Also, they are rarely as unlikely, although the educated man sneers at them — actually, their strength lies in their probability, at least to some people, and this probability would rather seem to be increased than diminished to those who live far from where the events are said to have taken place. A substantial quantity of such hearsay actually deal with the behavior of strangers, of people with very different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, these modern hearsay fail not only at the second criterion, but also at the first and fifth.

Space aliensA vaguely different type of modern hearsay are those reporting about space aliens abducting people, probing them and so forth. They would readily fit the first and fifth criteria, being both elaborate and highly unlikely stories, although failing the second. Often they prove to conflict also with criterion six — there is in many cases an author to be traced, a book or a newspaper article, or somebody claiming to be the very victim of such an abduction and therefore the originator of the story.

MisconceptionThe most confusing use of the term myth is in expressions as, say, 'the myth of the happy millionaire' or 'the myth of the harmless cigarette'. The word misconception would be more appropriate, adding widespread to it, if that be the case. As a myth it cannot pass any of the criteria above, except maybe for the fourth, but its most alarming shortcoming is the fact that it lacks a story, a series of events leading to a change.Applications of the six criteria for myth:

The dragonNow, these six criteria create a number of implications as to the nature and dynamics of myths, many of which have been extensively discussed in literature on the subject, although on different grounds. Demanding myths to be elaborate stories as opposed to simple statements of a somewhat metaphysical nature, excludes not only the modern hearsay mentioned above, but also all kinds of delusions or beliefs of the past, which might be of mythological fragrance. Thus, the dragon is not a myth, although a mythological creature, but stories about it may very well be. A phenomenon in itself is never a myth, nor is a number of phenomena however intricately linked to each other — unless there is a process of events going on between them, having a beginning and, if not a definite end, some kind of outcome. Something leads to something else, or something happens and then something else. It must be possible to pinpoint events on a timescale.A mythological ingredient without the story is never a myth in itself, but rather what can be labeled a mythical object. Then, what passes all criteria but the first we can probably classify as a mythical object.

Distant pastThe significance of time appears also in the second criterion. If the events of the story do not belong to the past, a distant past at that, it cannot meaningfully be described as a myth. The key here is the distance, without which the non-fictional claim of the fourth and the unlikeliness of the fifth criterion would just make it silly — a tale about a dragon flying through the avenues of Manhattan or Ahasverus riding its subway would be laughed at, if presented as anything but pure fiction. Such figures in a setting of the past, though, would not demand of the tale to declare itself as fiction — if that past is enough distant.Why so? It is the joint mechanisms of criteria four and five — the former demanding that somewhere, sometime, it must have been likely that people might have believed the tale to be non-fictional, although, according to the latter criterion, people of another time or place, would definitely not. It is not a myth if it cannot be believed by some and strongly disbelieved by others. Then, time is not the only distance making this possible, a geographical distance or a cultural one would serve just as well. A tale can be believable to one ethnic group and completely rejected by another, both of them living in the same city. But if the tale in question has a contemporary setting, it makes much more sense to all but the believers in it to call it superstition. A tale, then, passing all criteria but the second, would be something of the kind of the crocodile mentioned above, and preferably categorized as superstitious hearsay or modern folklore.

Greater magnitudeThe third criterion demands of the tale to deal with things of greater magnitude than everyday life — an adventure, a fabulous event, something never to be forgotten. Certainly, without the fulfillment of this criterion, a tale would not remain with us through the centuries, but also, it is very hard to see how it would otherwise accomplish the unlikeliness demanded in criterion five.For example, a story of a woman giving birth to a child is not in itself material for a myth, but if that which she gives birth to is a bull, then both the third and the fifth criteria are met. The significance of the third criterion may often enough be right at the paradoxical contradiction between the non-fictional claim of the fourth and the unlikeliness of the fifth, but not necessarily so. Many myths are not wonderful in the sense of that contradiction, but in the significance the events in them are said to have to the world thereafter.

SignificanceIn many cases the significance lies in the multitude of symbolic interpretations, or right out poetic expressions, which can be made with them. Icarus falls from the sky, again and again, as a metaphor in numerous discussions, a motif in paintings, a statement in philosophy, through centuries without end. The significance of the story is not one and the same, in all these uses of it, nor is the symbol of it presented in a homogenous way — but the fact of its significance is hardly ever debated.

Icarus. Wall painting by the author. An insignificant story, meeting with all the other criteria, would first of all not be remembered for very long, nor would it easily manage criterion five, but if it did, it would more readily be called a hearsay. Definitions of the term myth often demand the presence of divine or in other ways supernatural creatures — it is to a large extent this demand I have modified in formulating the third criterion.

SupernaturalWhat is divine or supernatural is in itself very complicated to decide, and very often dependent on the cultural heritage of the individual listener — which would more readily place this demand in the fourth or fifth criterion. If a tale meets with the demands in those two criteria, being believable by some and not at all by others, it needs not contain supernatural creatures — whatever that may be — to pass as myth. Icarus may have performed a wonderful feat, flying with the wings of his father's making, but neither he nor the father can be called supernatural — even though their deeds were. Nor is there anything necessarily supernatural about the myth of Atlantis — yet, in our eyes, highly unlikely, thereby again a circumstance to be tried on the fifth criterion.

Non-fictionThe non-fictional claim of criterion four may sometimes be unclear, needing to be read between the lines, so to speak. A novelist may use all his skills to support the illusion, never once in his book revealing that it is all made up, but still there is a statement somewhere in the narrative, proclaiming it as fiction. One might even say that this is true also of novels expressly based on real events — the fictional nature of the story dominates, so that the reader tends to perceive it all as closer to the world of the imagination than that of real life, even if the setting is one of well-known facts. Also stories without any known author can have this air of fiction about them — an impression that they have never been regarded as anything but fiction. If that be the case, and they meet with all the other five criteria, we would not call them myths, but fairytales.The fifth criterion, the strong sense of unlikeliness in the eyes of people of other cultures than the one of the tale´s origin, shows its importance in the way it is intermingled with the workings of several of the other criteria. Here is the touch of the supernatural, of wonders and miracles, without which a tale would not be much of a myth. If all the criteria except the fifth are met, a proper term for it would be tale, a traditional story about an adventurous, fascinating past — heroic warriors, valiant nobles, individuals as well as whole tribes on a glorious quest.

Touch of magicSuch tales we find in abundance, but only if they contain important elements making them highly unbelievable to other people do they qualify as myths — a touch of magic, if you will. Without this criterion, any example of traditional history and any orally transmitted story of days long gone, would be a myth. Somewhat contrary to the other criteria, this one does not exclude a group of stories, but narrows down to a specific fraction of it: some tales are myths, but all myths are tales.Fairytales, mentioned in regard to criterion four, are certainly also tales, but a different fraction from that of myths: no myths are fairytales.

Canterbury TalesAll types of tales are stories, of course, but a tale in the traditional meaning does not have its origin with a known author. The Canterbury Tales were all put in writing by Chaucer, but in a way where he claims not to be the inventor of them — whatever his readers may think of it. Thereby, if his claim is the least probable, those tales would pass the sixth criterion, but rarely the fifth and only occasionally the third. His tales, then, are best described as anecdotes. In case they were inventions of his imagination, though, the term anecdote becomes awkward, since it implies having actually taken place. In this way, the anecdote does, as well as the myth, need to pass the sixth criterion. Stories which do comply with all criteria but the sixth, can simply be called fiction.Then we find the following forms emerging, if all criteria but one are fulfilled. When all criteria but one are met:

NextExplanatory and Adventure MythsThe Logics of MythBasic Patterns of Creation Myths

This article was originally written in 1999 for a seminar at the Department of History of Ideas, Lund University, as a part of my dissertation in progress on Creation Myths and their patterns of thought. Published on the web on September 6, 2001.

MENUCreation Myths Around the WorldHow stories of the beginning began.

The Meanings of MythologyTheories through history about myth and fable.

Archetypes in MythsThe mythological symbols and what they stand for.

The Logics of MythPatterns of creation.

ContactAbout Cookies

CREATION MYTHS IN DEPTHCreation in Rig Veda 10:129The paradox of origin, according to an Indian myth.

Genesis 1The first creation story of the bible scrutinized.

Enuma ElishThe ancient Babylonian creation myth.

Xingu Creation of ManThe insoluble solitude of gods and humans.

ON MY OTHER WEBSITESPsychoanalysis of MythWhat Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung thought about myths, their origins and meanings.

Myth of CreationAn introduction to the subject of creation myths and the patterns of thought they reveal.

Cosmos of the AncientsWhat the Greek philosophers believed about the cosmos, their religion and their gods.

Life EnergyThe many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

TaoisticTaoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy of life explained. Also, the complete classic text Tao Te Ching online.

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Sunday Brunch with the World Maker

Sunday Brunch with the World Maker Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd