Xingu Creation of ManInsoluble Solitude

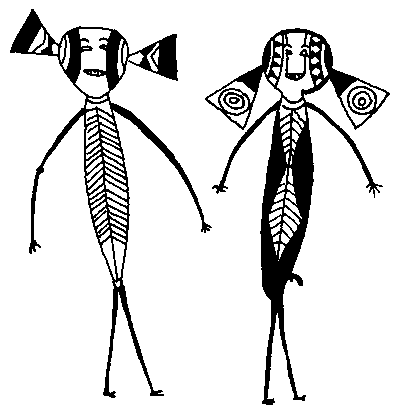

The Xingu Indians, living around the river in Brazil given their name, also have myths that contemplate various misfortunes in the laws by which the world operates ever since primordial time.

Already the creation of the first man is a story that must be called a tragedy. In the words of the Swedish author Hjalmar Söderberg: “I believe in the desires of the flesh and the soul's incurable loneliness.” Here is the Xingu story of how man was created (from Villas Boas, p. 53):

Creation of the First ManIn the beginning there was only Mavutsinim. No one lived with him. He had no wife. He had no son, nor did he have any relatives. He was all alone.One day he turned a shell into a woman, and he married her. When his son was born, he asked his wife, "Is it a man or a woman?" "It is a man." "I'll take him with me." Then he left. The boy's mother cried and went back to her village, the lagoon, where she turned into a shell again. "We are the grandchildren of Mavutsinim's son", say the indians.

The Villas Boas brothers first met the Xingu in 1946 and spent a large part of the following 25 years in their company. The brothers struggled hard for the human rights of the Xingu population and were instrumental in Brazil proclaiming the territory a national park in 1961, whereby the conditions for the Xingu improved so that they could continue their way of life. It quickly led to the population increasing from just about a thousand when the Villas Boas brothers arrived to their territory.

Present day Brazil on the world map. The Xingu live around the Xingu river, named after them. The myth above is as close to a cosmogony as can be found in the collection of the Villas Boas book, as well as other source I have searched. I found nothing about the birth of the world. It would seem that to the Xingu, the world is eternal although mankind is not. Above is the story about the first man. They also have a myth about the end of mankind, and our world along with it (Villas Boas, p. 249): Finally Sinaá showed the Juruna visitor an enormous forked stick that supported the sky and said, “The day our people die out entirely, I will pull this down, and the sky will collapse, and all people will disappear. That will be the end of everything.”

Hidden CosmologyIt's unusual that a culture has an idea about the birth and end of mankind, but not one about the emergence of the world. Although the Villas Boas brothers spent so much time with the Xingu and were increasingly trusted by them, it's possible that they were not introduced to the cosmology of the Xingu.In their book, the brothers readily admit to the difficulty of gathering trustworthy material from the Xingu population (Villas Boas, p. 49f): One of the most difficult things in obtaining this kind of data is to find the best informant. An Indian who speaks our language well and who readily offers to tell us stories or reveal information is precisely the least trustworthy for this purpose. True informants never come forward on their own, they speak only their own language, and when they are questioned, they even draw back. Furthermore, there are never more than one or two true trustees of the spiritual culture in each village. There are many examples of cultures in which cosmological myths are highly guarded secrets, hidden from visitors, sometimes even from all but the oldest shaman. That has been the case through the many centuries the Saami of northern Scandinavia have interacted with neighboring people, not without complications. Apart from a drunken slip of the tongue in a conversation with a priest in the mid-18th century, the Saami have succeeded in keeping their cosmology to themselves (Högström, p. 57f). The rule of secrecy is also the case with the Aborigine of Australia and other cultures. When Marcel Griaule finally got to learn the enormously intricate cosmology of the Dogon in Africa, after serving as their doctor for many years, he was completely surprised and amazed at its complexity (Griaule 1948). We don't know, but the possibility remains that the Xingu have a cosmology, which they only share among themselves. Usually, the reason for such secrecy seems to be a belief in cosmological knowledge containing great power, hazardous to spread beyond the community.

Mavutsinim the World Creator?To the knowledge of the Villas Boas brothers, Mavutsinim is the most primordial of deities, father of the first man as well as of the mother to the sun and the moon (Villas Boas, p. 57ff). But a creator of the world he seems not to be. I would still say that he is, though, from the indications of the myth above.The utter solitude of Mavutsinim, elaborately described in the opening lines of the myth, suggest that there can have been no one else responsible for the world creation. In just about every creation myth there is some kind of being responsible for the act of world creation – simply because in the framework of myth and the mind of primordial man, that action needs an agent, a will to act, which must come from a conscious being. Who else but Mavutsinim, who is all alone in the beginning? I doubt that the Xingu believe in an eternal, uncreated world. Then they might just as well have believed the same about mankind and many other things of which their myths describe their beginning. The sun and moon are born, daylight is brought to the world of the Xingu – so why shouldn't they ask themselves if perchance the whole world had a beginning? Most other cultures have done so. There is another indicator of the Xingu contemplating some kind of creation: The myth above plays on the problem of how to create something new out of something else, a paradox that has occupied the minds behind so many creation myths. Mavutsinim is one of a kind, since he was the very first of any kind. So, how to reproduce at all? He goes to the river, as do the Xingu for their livelihood. They are fishermen, although they also hunt some game and have agriculture (Smith), the latter of which is the most recent. They would be quite comfortable with the idea of life stemming from the waters. That they share with a great number of cultures, in which a primordial water is seen as the source out of which the world itself is pulled. This body of water is regarded as eternal, though not always explicitly so. Its ever-presence is something so natural to many cultures of old, their myths present it as self-evident, never even commenting it. Usually, this primordial water is the sea, but that was out of reach to the Xingu. Their lives revolve around the river, and have done so for very long. Although its water floats as if from an endless source, the river may not give as impressive an image of eternity as the sea. It's still much more persistent than plants and animals on the land surrounding it. So, the Xingu would assume that the river may not have preceded land, but certainly everything on it.

Opening the ShellThat's why the Xingu have Mavutsinim go to the river when searching for a mate with whom to reproduce. Of course he finds none of his own kind, since he is the very first and has not multiplied yet. He has to make do with something else. He chooses a shell, turning it into a woman. This power of metamorphosis is another indicator of Mavutsinim being the closest to a creator god of the Xingu. It's also worth noticing that the Xingu, although fishermen, don't eat shellfish (Smith), which may be linked to this myth. They would not feast on the species of their ancestral mother.

Where the myth speaks of marriage, I presume that copulation or some other means of procreation is intended. What follows makes it evident that Mavutsinim has little intention of a lasting relation. The Villas Boas brothers may have polished the language used for their Brazilian readers of a Catholic tradition. They would not be the first writers editing their report for such reasons. Old myths can be quite a lot more outspoken and blunt than what has been regarded as proper in the Western tradition. Now, once the boy is born, Mavutsinim takes him away. The woman is left alone, crying. Then she returns to the lagoon becoming a shell again. The shell that opened has closed.

MelancholiaThis Xingu creation of man is a sad one, indeed. It has an air of futility and melancholia. The merciless rhythm of life: We are born, we leave our parents, we give birth and see our children leave us, and then we die. These facts of life are symbolically represented in this short story. There is no exception. Each one who leaves his mother's womb will soon leave her life as well, either by departing or at the moment her life ends.The Xingu myth contains both options. When the mother returns to the lagoon, her origin, and becomes a clam again, she leaves the world of living men altogether. It's as definite as death, where no link of any kind remains. The myth displays a world of male dominance and complete lack of empathy towards woman. But doing so, the story pinpoints that cruelty. She is portrayed as a victim, deserving our sympathy, whereas Mavutsinim can only inspire disgust. But he's the creator of mankind, so his perspective is another. He is not intentionally cruel, although his action is despicable. Mavutsinim is indifferent, his mind occupied by an intention of a magnitude that makes him blind to the consequences at that moment. He has a whole species to create. The myth also makes it clear that he does so in order to end his loneliness. Who wouldn't?

SourcesClick the source to see the book at Amazon.

Now, a MovieDuring the research for the above text I discovered that the Villas Boas brothers' struggle for the Xingu people has become a movie this year (2012). Indeed, a story worth telling. Here's the trailer for it:

MENUCreation Myths Around the WorldHow stories of the beginning began.

The Meanings of MythologyTheories through history about myth and fable.

Archetypes in MythsThe mythological symbols and what they stand for.

The Logics of MythPatterns of creation.

ContactAbout Cookies

CREATION MYTHS IN DEPTHCreation in Rig Veda 10:129The paradox of origin, according to an Indian myth.

Genesis 1The first creation story of the bible scrutinized.

Enuma ElishThe ancient Babylonian creation myth.

Xingu Creation of ManThe insoluble solitude of gods and humans.

ON MY OTHER WEBSITESPsychoanalysis of MythWhat Sigmund Freud and C. G. Jung thought about myths, their origins and meanings.

Myth of CreationAn introduction to the subject of creation myths and the patterns of thought they reveal.

Cosmos of the AncientsWhat the Greek philosophers believed about the cosmos, their religion and their gods.

Life EnergyThe many ancient and modern life force beliefs all over the world explained and compared.

TaoisticTaoism, the ancient Chinese philosophy of life explained. Also, the complete classic text Tao Te Ching online.

|

Archetypes of Mythology

Archetypes of Mythology Psychoanalysis of Mythology

Psychoanalysis of Mythology Cosmos of the Ancients

Cosmos of the Ancients Life Energy Encyclopedia

Life Energy Encyclopedia Sunday Brunch with the World Maker

Sunday Brunch with the World Maker Fake Lao Tzu Quotes

Fake Lao Tzu Quotes Stefan Stenudd

Stefan Stenudd